Finishing off a week of lengthy landscape treatises, we turn to renown sculptor and at times landscape artist Isamu Noguchi.

Isamu Noguchi was a unique figure among American artists of the twentieth century. He excelled in a wide range of genres and in countless media, in a career that spanned genres from the development of Modernism through Post Modernism. He created intriguing sculpture pieces, stage sets, paper lanterns, public spaces, landscape sculptures and architecture. His use of media extended from his favorite stone, to wood, metal, clay, mixed materials, and most importantly space. It was in the dimension of space that Noguchi thrived and his ability to bring art into the landscape was the hallmark of his career . Whether his work was a simple piece of carved stone or acres of a public park, Noguchi had an amazing flair for conceptualizing and designing things that were spatially engaging and which broke out of the box of traditional sculpture and art. Throughout his career he was always pushing the edge of what was considered art, and searching for ways to explore, and redefine personally what art indeed was. His experimentation, relentless drive and passion to create, pushed the limits of the art establishment throughout his over sixty-year career. With the larger canvas of the landscape, his stone sculptures reach a new and more powerful significance. Drawing on a rich cultural heritage and experiences from Japan, the United States, and time spent in Europe, Noguchi transitioned techniques and themes found in his sculpture into larger landscape projects.

His forays in the landscape strayed from the traditional staples of sculpture. His landscape compositions are a unique fusion of both art and landscape. An examination of Noguchi’s origins places him in the proper perspective. Throughout his career, Noguchi sought to define himself and his work through a unique blending of his own personal context, in concert with his own artist’s prerogative. Noguchi was born in Los Angeles in 1904, the son of a Japanese poet, Yone Noguchi and an Irish-American writer, Leonie Gilmore. This duality of cultural backgrounds, heritage from his childhood spent in Japan, and later experience living in the United States would shape Isamu’s life and work. Noguchi referred to himself as an outsider because of his mixed-heritage and a less than stable family life that included a strained relationship with his father. Uneasiness and a lack of security shaped Noguchi’s life. According to Bruce Altshuler in his book on Noguchi, “Noguchi said he could feel at home everywhere because he was at home nowhere.” Perhaps it was this uneasiness, one that sat at the very core of his being, which would signal the purpose for his immense and diverse life’s work as an artist.

Noguchi’s landscapes were far reaching in their scope, representative of the currents of the rest of his art as a whole, and spanned the many decades of his career. From his landscape Play Mountain (1934), which was a conceptual idea for a children’s playground that he conceived of early in his career, to his later works of landscape artistry, Noguchi maintained and continued to develop a refined design style and interaction between his art and the landscape. As time progressed, he polished his skills of combining sculptural elements with elements of the larger landscape.

CALIFORNIA SCENARIO

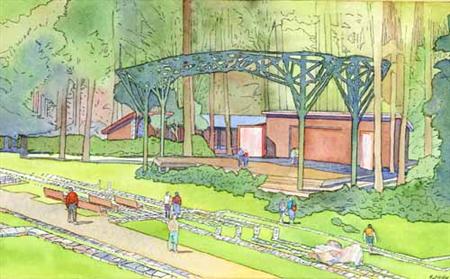

Of particular distinction is Noguchi’s work at what he entitled California Scenario (1980-82). It is here, at the end of his career, that Noguchi perfected his art. With an artists’ hand Noguchi crafted this amazing work of plant, water, and stone. Just off of the 405 freeway in Costa Mesa, California there are two clusters of uninspired office buildings sitting close to the freeway. To the casual driver, or unknowing passerby, this office park, the South Coast Plaza, seems to be of little distinction. Similar developments are commonplace throughout the Southern California landscape. Entering into the complex in the direction of the freeway reveals subtle changes. Paths of flagstone of a rose hue draw inward, hinting at something more. Continuing into this space, there is a fountain of stone, capped by stainless steel, marking the transition into a different spatial envelope. Here, sandwiched between two glass monoliths scraping the sky, sits a divine 1.6 acres. Here lies Noguchi’s scenario.

Noguchi’s scenario is the embodiment of California through an artist’s eyes. Using primitive and somewhat simple forms and representations, Noguchi captured in this work the essence of California, while at the same time maintaining a purity and clarity in sculptural form.

California Scenario is a composition of balances. Each element, each factor in the overall composition aids the larger message, while any factor solely by itself would illustrate only a diluted meaning. There is energy in this place, and it is odd that what is considered a landmark of landscape design and artistry should sit in such an inauspicious setting. The common user of this space may be a cigarette indulgent employee housed in the nearby office buildings for which Noguchi’s artistry is unrealized; yet perhaps even the most unknowing viewer is affected by Noguchi’s Zen-like composition. The space seems to command a certain recognition by those whose pass through it. This design is executed extremely well as the spatial layout and symbolic meaning flow together in perfect harmony.

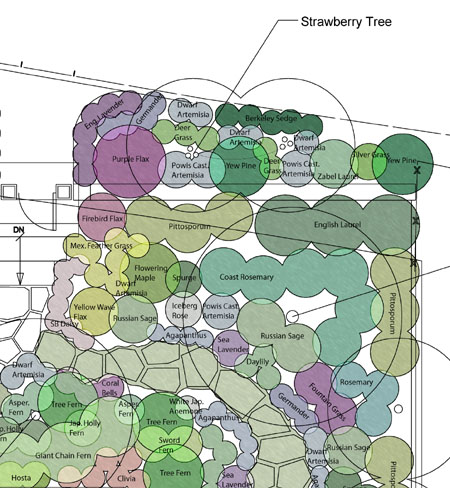

The forms and symbols chosen to represent California in the work reflect both a basic understanding of archetypal units of California, and of an overall mystery. A stack of boulders, hand picked from the California desert is one such symbol. The individual piece titled by Noguchi, The Spirit of the Lima Bean, is both a wonder of construction and visually remarkable. Simple in its meaning, the large grouping of rocks reflects the essence of the Lima Bean, the crop that was farmed in the area prior to development. The rest of the meanings in the work are of the same simplicity, yet they maintain effectively what Noguchi was trying to accomplish. A large sculptural form to represent the mountains, stream paths to represent the valleys and to show the movement of water, a stand of redwoods to represent the mountains. In a corner a large mound of sand and cacti represent the desert. Each of these isolated elements is effective in its simplicity. Just the two words California Scenario, and the meanings of the basic elements become clear and command appreciation. Yet, like all great works of art, not only can the meaning differ with the individual, but also it is clear that Noguchi conceptualized something more complex.

Perhaps the best thing about the space is it forces no messages. Some may see a stack of rocks where there is a small ledge perfect to sit and smoke a cigarette; others may see the broadly sweeping and diversified California landscape. Noguchi’s hidden jewel, enclosed in industrialism, sits still today as it did when Noguchi first installed it, slowly aging and growing wilder by the day.

Noguchi was an amazing artist not because he was just a great sculptor. He achieved greatness through an all-consuming passion for his art, and a unique appeal. As the Latin America Daily Post referred to him so eloquently, “He is a curator. A curator of time and space. A creator of a continuum of the universe that is only known to him.” For those preoccupied with landscape and with space, he did something magical. He created spaces of living art and sculpture, greater than any landscape design or piece of chiseled rock alone. He created places of meaning, metaphors beyond the scope of traditional art.

GREATER SIGNIFICANCE

Clearly Noguchi did not want to leave the world of art, just redefine its boundaries. In an interview with Noguchi in 1981, the Latin American Daily Post beautifully articulated the artist’s ability for capturing space, “This is a man who has brought clarity to natures order. It is a vision of time and space made tangible by one who lives in the present, but scans all and perhaps more, of what is Homo sapiens.”

Noguchi in his landscape works created an outstanding sense of concept, often tapping into mythology from around the world, which gave a human level of meaning to his often abstract stone and sculptural works.

Isamu Noguchi grasped the concept of the Arts, not art alone, are a reflection of human life and existence. Art is not anything but an opinion, created by man for our own amusement, inspiration, and expression. Noguchi beautifully defined and created a wide range of works in his art, taking the known boundaries of what was considered art and pushing them further. This is what he did in the landscape, using the principle mediums of stone, form and space. Interestingly, Noguchi was not widely accepted in the art world as much as he was in the world of architecture and design. This isolation did not faze Noguchi though, he was resolved to take sculpture and artistry to the next level. Bruce Altshuler in his book on Noguchi eloquently surmises the aims of Noguchi’s landscape art. “For Noguchi, in the chaotic void of the modern world- a world without religion and threatened with nuclear destruction- meaning must be created, and its creation required spaces that would encourage social ritual. The structuring of those spaces was to be

the new calling of sculpture, and it reining metaphor was the garden.

Indeed Noguchi’s aim had multiple objectives. He sought to further sculpture while at the same time creating spaces and using the power of external three-dimensional space. He also sought a fellowship with nature, this was the reason why he had an affinity with stone and its expression in both the natural and man-made landscape. The article in the Latin American Daily Post expounds on this desire,

“This continuum of Isamu Noguchi is a realm of time and space which he describes with a halting simplicity and directness. His is a modest statement that it is nature, not man who prevails… [Noguchi represents] a man and his vision of the kinetics of nature. Sky, light, shadow, water, occasionally flora, and stone. Almost always stone.”

Despite all his works, in his essence Noguchi was a stone sculptor. Yet as stone is both natural and expressed in space, this did not preclude him from pursuing and designing places to express his sculpture. In the end this is exactly what Noguchi did, he created space in the landscape to display his sculpture of stone and space together as one.

Through his work with the landscape, Noguchi expanded his own artistry, and left a legacy far beyond the stone of the studio. In his landscape compositions, scattered from Paris to Japan and points in between, Noguchi created a theater for his legions of stone; a wonderful and mysterious tapestry through which the stone could be brought to life. — Noguchi’s carvings through the larger landscape transcend what he could do alone with any artistic medium or with any landscape by itself. Noguchi gained the rarified distinction of landscape artist. Perhaps Noguchi didn’t even see himself by this title, but he did have the realization that the landscape afforded him a much wider, sweeping appeal than through some stuffy museum alone.

California Scenario – “The Spirit of the Lima Bean”

Sources

1. Altshuler, Bruce. Noguchi. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers. 1994.

2. Ashton, Dore. Noguchi East and West. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1992.

3. Cummings, Paul. Artists in Their Own Words. New York: St. Martins Press. 1979.

4. Latin America Daily Post. “Isamu Noguchi Neither An Artist Nor A

Sculptor, But A Curator Of Time And Space.” Brazil. 1981

5. Noguchi, Isamu. The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum. New York: Harry

N. Abrams Inc. 1987.

6. Torres, Ana Maria. Isamu Noguchi: A Study of Space. New York. Monacelli Press. 2000.

7. Tracy, Robert. Spaces of the Mind: Isamu Noguchi’s Dance Designs. New York: Proscenium Publishers. 2001.